In Defense of Boring Games

August 18, 2025

But most of the interesting art of our time is boring (…) Maybe art has to be boring, now.

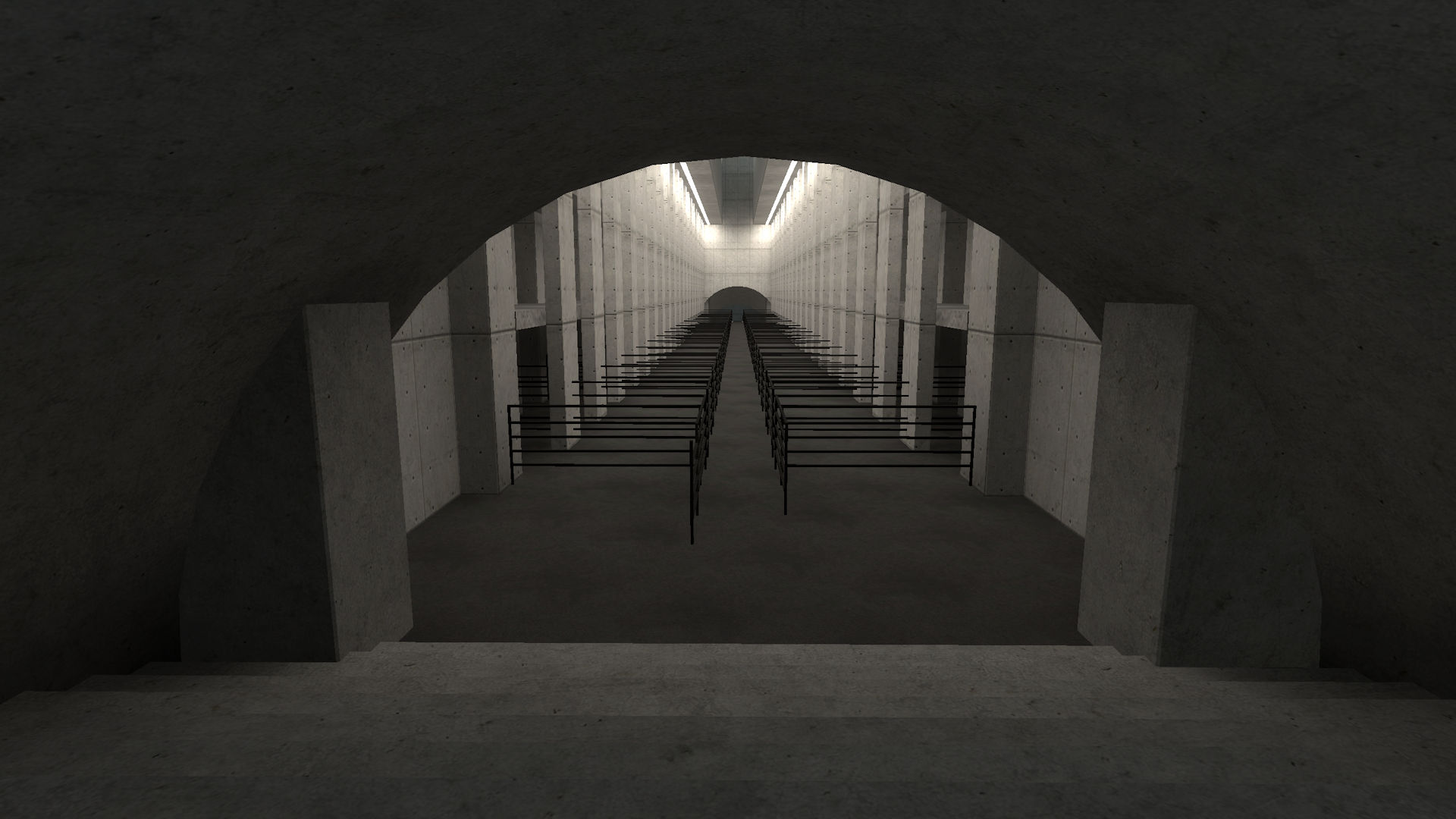

There’s a scene from The Beginner’s Guide (2015) that I’ve been thinking about a lot recently.This post is based on a talk I gave at the 2025 NarraScope conference. The game presents itself as a series of maps created by a reclusive game developer known as Coda, which have subsequently been compiled and released to the public by one of Coda’s fans named Davey. One of those maps contains an empty Brutalist prison where the player is guided along a fenced off path into a small cell that slams shut behind them. Davey, taking the role of narrator and curator, explains that in the original game, the door would stay shut for a full hour, preventing any further progress until it opens. But Davey has modified the game, opening the door after only a few seconds in the name of making the game, in his words, “playable.” There is a common-sensical logic behind his decision: waiting around for an hour is boring, and boredom isn’t fun. It’s easy to conclude that boring scenes are therefore flaws that needs to be fixed. Davey never considers, however, that the boredom of waiting in a prison cell might be a meaningful, even crucial, aspect of the gameplay that he has unwittingly sabotaged. What would happen, by contrast, if the game really did make players wait the whole hour: Would they give up in frustration? Would they Alt-Tab over to their social media feeds until something happened? Or would they sit there with the game, and if they did, what might they make of that experience?

The Purpose of Boredom

Like all tools, boredom can be misused, and of course not all games that evoke boredom are automatically “good.” But when thoughtfully integrated into a game’s design, I’d argue that boredom can profoundly shift how players engage with the experience presented to them by encouraging a player-led process of reflective interpretation. This impetus to create meaning emerges from the fundamental experience of boredom itself, which consists of two key parts: the first is a feeling of not being satisfactorily engaged in a given situation (e.g. it’s overly predictable, it allows for limited autonomy/challenge, etc.).In this admittedly simplified definition, I’m drawing on The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom (Routledge, 2024), especially Andreas Elpidorou’s “The Nature and Value of Boredom,” Eric Igou et al.’s “Boredom and the Quest for Meaning,” and Wanja Wolff et al.’s “Same Same but Different: What is Boredom Actually?” Whatever the reason, being bored is a highly unpleasant state to be in, and that leads to the second component of boredom, which is an open-ended desire to change your situation to become less boring. It’s not that you really want to be doing something else in particular, but that you want to do anything else. As a result, boredom often pushes people to seek out new experiences, for good or ill. It can encourage people to try new hobbies, like how half the Earth’s population took up baking during the COVID pandemic. It can also encourage people to get drunk and start a fist-fight with whoever’s in striking distance, not because it’s a good idea, but because it’s at least not boring.

While Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad has been praised by many critics, it’s also been a lightning-rod for accusations of being “boring,” alongside related adjectives like “confusing” and “pretentious.” Obviously the film is a masterpiece, and I will fight anyone who says otherwise.

Please don’t actually fight me. I am physically weak and also conflict-averse.

“Boring” Art

But with this definition as our starting point, it’s still not clear why we would want works of art that bore their audiences. If anything, it seems like art is supposed to help relieve us of boredom, not contribute to it. And yet, in just about any artistic medium you look at, you’ll find no shortage of works that are deliberately made to provoke a sensation of boredom. Marcel Duchamp’s “readymade” sculptures are just regular, utilitarian objects like urinals and bike wheels. Alain Robbe-Grillet’s novels eschew linear narratives in favor of lengthy, mechanically precise descriptions of mundane scenes. In reflecting on this phenomenon, Susan Sontag even goes so far as to claim that “most of the interesting art of our time is boring (…) Maybe art has to be boring, now.” For Sontag, boredom plays a crucial role in shifting the way audiences pay attention to a work. We always approach art with a pre-existing horizon of expectations for how we’re supposed to engage with it, what we’re supposed to pay attention to, how we’re supposed to make sense of what’s being presented to us. But “boring” art can break out from these expectations by not allowing the audience to meaningfully engage with a work in conventional ways. This is why boring art gives us sculptures that aren’t beautiful, narratives without traditional plots or characters—I’m aware that, as of the time of writing, the internet has decided m-dashes are a sign of GenAI writing. I categorically reject this slander against a perfectly innocent article of punctuation, and will not be coerced into avoiding it. because it doesn’t want to be understood within those conventional frameworks. By minimizing or disordering these expected features, boring art can produce an aesthetic shock in which the audience initially doesn’t know how to even respond to what is being presented to them.Sianne Ngai refers to this shock as “stuplimity,” a portmanteau of “stupefy” and “sublimity” that captures the potentially overwhelming nature of this encounter with aesthetic boredom. See her article “Stuplimity: Shock and Boredom in Twentieth-Century Aesthetics” in Postmodern Culture, vol. 10 no. 2, 2000. It is only through this initial shock that we start to develop new interpretive strategies, learn to see new forms of coherence. In talking about “boring art,” then, I mean something distinct from art that is boring in the more pejorative sense of the term. I’m not talking about art that tries to be conventionally interesting and simply fails, but rather art that deliberately thwarts conventional interest.

The particular aesthetics of boredom will, of course, vary from medium to medium. In the case of video games, we’ve already seen an instance of aesthetic boredom in The Beginner’s Guide, albeit one that has been abruptly cut short. The prison cell where players finds themselves stuck is a space designed to produce boredom, and we can discern several interlocking features that combine to create this effect. The cell, for instance, provides very limited space to move around in, and no other form of interactivity. There’s also a long delay between player intention and result, since at least in Coda’s version, they would have to wait around for an hour before being able to leave the cell. Finally, there’s not much in the way of visual interest to hold the player’s attention, with monochrome grey textures repeated across almost every visible surface.

But similar to what we’ve seen already in the psychological studies of boredom, this search for an escape from boredom can easily go wrong: the player could quit playing altogether, or they could just let their mind wander and start thinking about how they really need to pick up cat litter from the grocery store. In either case, the player has already stopped meaningfully engaging with the game. To prevent this outcome, a game needs to provide hooks that can prompt and guide the player’s thoughts without defining the exact content of those thoughts in advance. When done well, this can create a kind of dialogue between player and game that is built on a mutual sense of trust: the player trusts that the game will reward their efforts to think about it in a new light, and the game trusts that the player will be able to create meaning out of the elements presented to them.

The Graveyard

Tale of Tales’ The Graveyard (2008) is a game that depends on this kind of dialogue. It takes a decidedly minimalist approach to gameplay: you control an old woman as she walks down a linear path through a graveyard, sits down for a few minutes while a song plays in the background, then gets up again and walks back out the way she came. Her walking pace is incredibly slow, such that even though you can immediately see the bench that you need to reach, it will take around two minutes of holding down the forward button for her to actually reach it, and then another two minutes to leave. Clearly, we’re not meant to approach the experience as we would a more traditional game, and the Steam description explicitly encourages players to adjust their frame of reference accordingly: “It’s more like an explorable painting than an actual game. An experiment with poetry and storytelling but without words.” The conceptual categories of “explorable painting” and “experimental poetry” help to prompt the player’s attention along certain paths, focusing on audio and visual design above mechanical decision-making, metaphorical and associative meaning above literal plot.

There isn’t really a clear moral to the story, nor any secret meaning to decode, but there is plenty of material ripe for analysis. One common line of interpretation about the game occurs on a thematic level, reflecting on themes of aging, death, and memory that are presented in the game. From this perspective, the limited mobility of the protagonist draws attention to the physicality of her body, the effort that is required for her to accomplish seemingly trivial tasks. The song that plays while she’s sitting down also helps to contextualize the theme of death as a matter-of-fact occurrence rather than something to be afraid of, with the off-kilter banjo and stuttering rhythms creating an almost playful quality that the musician, Gerry de Mol, has ambiguously described as “a slow death march for optimists.”This is from an interview with de Mol included in Tale of Tales’ detailed postmortem of the game.

Another line of interpreting The Graveyard looks instead to the game’s formal construction. In this sense, The Graveyard asks players the kinds of questions that boring art always entails: what expectations am I bringing to this experience? If this doesn’t feel like a “traditional” game, then what about it isn’t traditional, and is there a benefit to breaking from that tradition? The game’s restricted interactivity functions as a kind of “negative device,”I’m borrowing this term from Yuri Lotman, which he discusses in The Structure of the Artistic Text (Michigan Slavic Contributions, 1977). or an aesthetic element that is felt due to its absence in the work rather than its presence. By contrast, if The Graveyard were reimagined as, say, a short film, the questions of genre and interactivity would never arise because there wouldn’t have been an expectation of audience control in the first place.

To be clear, the particulars of any game are always potentially open to this style of close reading, but few games demand that the player interpret the significance of a walk cycle or background music as a core part of the experience. The game’s ludic boredom functions here in two ways: for one, it signals to the player that they should engage in interpretive reflection, even if they might not otherwise be inclined to do so, since there’s not much else the player can do. Importantly, it also limits the player’s cognitive load so that they actually have the space to think critically about the experience in real time without being distracted by the need for quick reflexes or strategic calculation. What the player takes away from this reflection will vary, but anyone willing to engage with the game on its own terms will probably leave with at least something to ponder.

The Longing

One of the reasons The Graveyard is able to sustain a player’s interpretive attention across its runtime is that it’s a short experience. At a little under 10 minutes, it gives enough time for the player to start thinking through what the game is doing without exhausting that line of reflection before the end credits role. It’s not clear that the same experience would benefit from being stretched out over an hour, and almost certain that it wouldn’t hold many players’ attention for a hundred hours. Studio Seufz’ The Longing (2020), by contrast, asks the player to wait over a year in real time to reach the end. You play as a shade who is asked by the king of a vast underground realm to wake him up in 400 days. A count-down timer starts, and you’re left with no further instructions. Whereas most in-game timers are designed to rush the player, creating an anxiety over time running out, here it does the opposite—both the player and the shade are faced with the anxiety of how to overcome that immense void of time without succumbing to deathly boredom.

Without anything else to do, the player is motivated to explore the surrounding area, but any forward progress is met with constant mechanical friction. Like the old woman in The Graveyard, the shade walks very slowly, sometimes taking over a minute to cross a single screen, and other basic actions take a similarly extended time: a door you come across early on takes several minutes to open, and digging tunnels in the rock will take hours. While the player has more choices about where to go and what to do than with the linear gameplay of The Graveyard, the game’s lethargic pace constantly forces the player to confront boredom on a mechanical level. At the same time, it does offer several mechanics to make the experience more bearable: in-game time and actions continue to progress even when the game isn’t running, for instance, and time will speed up when the shade is engaged in relaxing activities like reading or painting. So most playthroughs won’t actually take 400 full days, and most of that time will pass without the player’s involvement.

The shade isn’t quite so lucky. They remain trapped in the caves even when the player leaves, and they’ll occasionally comment on the unbearable emptiness of their existence. In the screenshot above, for instance, the shade remarks that “There must be something more to life than just waiting for things to happen.” Elsewhere, they comment on a nearby puddle by casually observing that it isn’t deep enough to drown themselves in. For the shade, this isn’t just a question of situational boredom, but rather a more pervasive existential boredom. As Lars Svedsen describes it, existential boredom emerges from the struggle to find a personal meaning to one’s life. We seek self-realization, but don’t know how to do achieve this goal or what kind of self to realize.See his book A Philosophy of Boredom (Reaktion Books, 2005). This is, essentially, the main conflict of the game, and it is up to the player to create meaning within the confines of this subterranean kingdom.

This task can be accomplished in small ways—for instance, while exploring you’ll find books for your library and decorations for your living quarters. The more time and energy you invest into customizing the shade’s home, the more this space takes on a personal importance. You can even read through the books that you find, many of which are public domain texts that seem to expand on themes that are already present in the game. If you have the shade read Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, for instance, you’re probably not just thinking about that title in isolation, but rather about Nietzsche’s philosophy in dialogue with the game’s existentialist concerns: what would he make of the shade’s situation, and what might the shade make of his arguments?Addressing these questions could, of course, occupy an entire article of its own. But in short: despite their shared interest in existentialist meaning-making, the shade is not a Nietzschean Übermensch, and that divergence seems important to understanding The Longing’s particular approach to existentialism.

The player’s quest for meaning also forces them to engage with broader ethical questions about the shade’s purpose. Do they have an obligation to follow the king’s instructions and wait the requisite 400 days, or should they instead try to escape to the surface? Both outcomes are possible, and the player has plenty of time to dwell on the matter. Moreover, in the game’s empty spaces, the fate of this fictional shade can easily slide into real-world introspection. I played through much of The Longing alone in my apartment as an unemployed PhD grad, and while it’s exploration of the terrifying aimlessness of existence didn’t make for a fun time, it did end up becoming an emotionally resonant experience for me. Obviously, my specific context isn’t generalizable to other players, but I’d be willing to bet that for most people, the game’s central question of “what should I be doing with my life” is not a purely abstract, fantastical concern.

Boredom and AAA Games

Now at this point, you might be thinking that my definition of “boring games” is necessarily limited to a small subset of weird indie games. There is perhaps some truth to that: Big AAA games can become boring through repetition or lack of originality, and they can sometimes even weaponize that boredom for the sake of opaque monetization systems (“skip the grind by buying FunBux!”), but in those cases boredom clearly isn’t functioning as an intentional artistic device. But there are high-profile titles that I think do approach boredom in a more thoughtful way. Much has been written, for instance, about the deliberately slow animations in Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018) that take several seconds to do things like picking herbs or skinning animals, actions that would be instantaneous in most other games.In their article “Press X to Wait: The Cultural Politics of Slow Game Time in Red Dead Redemption 2”, John Vanderhoef and Matthew Thomas Payne argue that RDR 2 subverts “hegemonic game time,” a form of temporality that valorizes speed, dominance and efficiency. It’s a compelling argument that dovetails in some respects with my own understanding of aesthetic boredom.

Then there’s the STALKER series, which frequently involve long treks through the games’ mutated landscapes where combat encounters are much less common than their open-world genre-mates. In STALKER 2 (2024), you’ll occasionally receive warning that an emission is going to hit, a kind of intense radiation storm that kills anybody left outside. This creates a potentially exciting moment as the player drops everything they’re doing and rushes to the nearest shelter, but once the player reaches safety, their only task is to… wait it out. It doesn’t take too long: depending on how quickly you get to cover, it’ll take a minute or two for the storm to pass. You might even find yourself in a new, unexplored building and use that time to investigate your surroundings, but more often you’ll just be stuck in a tiny hut or basement with nothing much to do. I don’t think this is a mistake on the developers’ part. A few minutes is just long enough that you start to feel the time passing, you start looking around for something to occupy your attention. It’s no accident that most shelters have prominent doors and windows that perfectly frame the storm roiling away outside. This is precisely what the game wants you to notice: the Zone as a sublime space of beauty and terror. After all, the main plot of the game is explicitly centered around what we should do about the Zone: should we leave it be, try to tame it? Or is it so dangerous that it needs to be destroyed altogether? While the player will ultimately make dramatic decisions about these questions, it’s really in the game’s empty, mechanically boring spaces where the player is most clearly encouraged to reflect on the Zone as a setting.

Conclusions

Making boring games is an inherently risky business, and there will be players who won’t want to engage with this kind of design. Some might be conceptually opposed to any game having the audacity to bore them, and others just won’t be in the mood for that sort of thing after a long, stressful day at work.Trust me, I used to work in customer service. I know the feeling. To make a boring game is to accept the fact that what you’re making isn’t for everybody, but could be intensely meaningful to players who are willing to engage with the experience in good faith. At the same time, the examples I’ve discussed above attest to the fact that boredom is a flexible design tool that can be adapted to suit a variety of contexts: it can be the star ingredient, or a subtle spice to counter-balance the cloying thrills of combat and conquest.

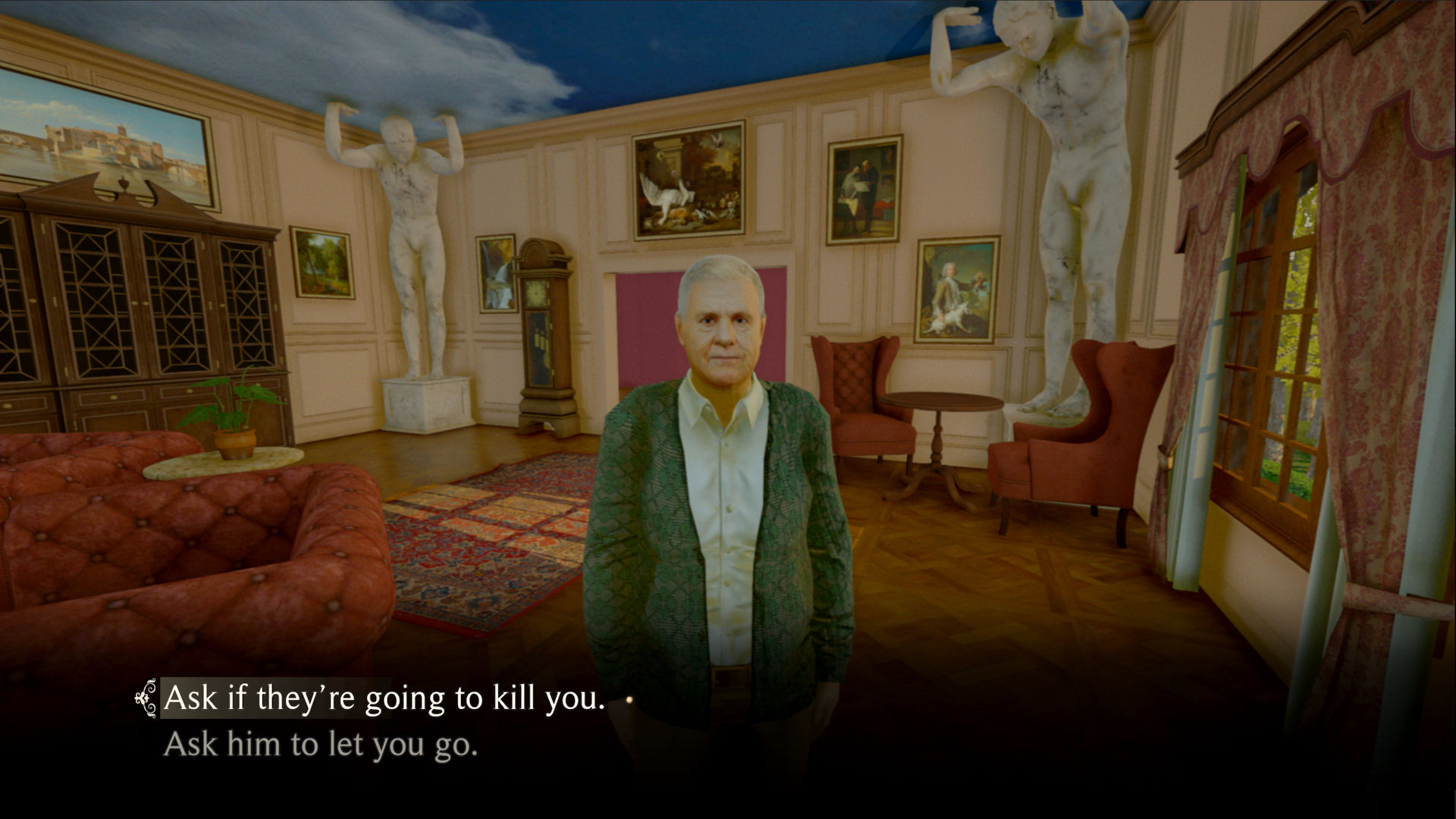

One of the reasons that boredom’s been on my mind is that it plays an important role in my own approach to game design. My upcoming game Beaux-Arts centers around the player being imprisoned in the living room of an isolated manor, chained to a radiator while the family and staff continue their daily lives around you. Boredom plays a key role in the game’s exploration of cruelty and justice by making this punishment seem “real” to the player in a way that I think games are uniquely suited to do.Being imprisoned in the context of a game that you can turn off at any point is obviously not the same as actual incarceration, hence the scare quotes around “real.” I mean simply that games can take away agency in ways that non-interactive media cannot. It creates space for the player to reflect on the details around them—the large collection of public-domain artwork that decorates the walls, for instance, was chosen with an eye for encouraging the player to connect it back to the game, often suggesting oblique or ironic parallels. I hope the game will succeed in earning players’ trust and producing meaningful responses, but since the game isn’t out yet, that hope remains hypothetical. Regardless, the point stands that I think boredom opens up a fascinating design space, and I want to see more games expand on those possibilities. Given the popular success of games like The Longing and The Graveyard (to say nothing of series like STALKER and Red Dead Redemption), I also believe there must be others who feel the same.